This article is excerpted from the newsletter and website of Bat World. Many thanks to the organization for allowing us to reprint!

In the five years since scientists first diagnosed White Nose Syndrome (WNS), the population of little brown bats in the northeast has plunged so dramatically (90 percent) that their very survival is now in question. Populations of the endangered Indiana bat are down 60 percent. Northern long-eared bat populations are down by a whopping 98 percent.

Since first being identified in New York state in 2006, it has spread to at least 18 states and three Canadian provinces in eastern North America, and has killed well over a million bats. Over 90% of the wintering bats in some New England caves and mines have died because of WNS. As the disease spreads into the Midwest and southeastern states, it threatens the federally endangered bats such as the Indiana bat, gray bat, Ozark big-eared bat, and our own Virginia big-eared bat.

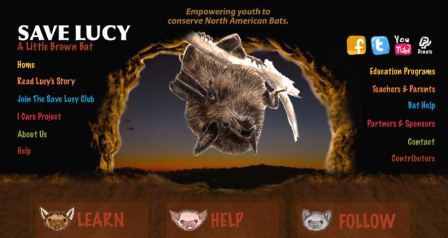

The Save Lucy Campaign is a Bat World Northern Virginia initiative. Find it at www.SaveLucytheBat.org

Geomyces destructans, the fungus that is to blame, was thought to be a cold loving fungus. However, some scientists now believe that the assumption that southern caves were too warm for the fungus is wrong. Many southern caves are still cool enough for Geomyces destructans to flourish, and in some regions may even be just warm enough for the fungus to spread even more quickly.

As the disease sweeps across the US, the agricultural value of bats is being brought more and more into the forefront. For instance, a recent study in Ohio shows potential losses of $23 million per county per year from increased insect damage. According to a recent study in the journal Science, Ohio farmers alone could suffer more than $740 million a year in agricultural losses, and possibly as much as $1.7 billion. These numbers are estimates based on crop acreage, the number of crop pests eaten by bats, the damage to crops that their feeding prevents, and the need, as a result, for farmers to spend less on pesticides.

The total value of bats to U.S. agriculture—and the potential loss from white-nose syndrome—is estimated to range from $3.7 billion to $53 billion a year, according to the study.

No one knows exactly how the fungus was introduced into the first cave in New York state, but experts believe it was brought in by someone visiting from Europe. The fungus has been found on bats in Germany, Switzerland, and Hungary, but these bats are surviving the infection. Researchers theorize that the fungus coevolved with the bats in Europe and North American bats have yet to build immunity.

The fungus invades the dermal layer of the bat‘s skin and destroys healthy tissue, and in the process wipes out hair follicles and sweat glands involved in regulating body temperature, respiration, and hydration. Wing tissues die as oxygen supplies diminish, then dehydration and starvation occurs.

The disease appears to be spreading primarily from bat to bat, although there is a risk that humans also may be spreading the disease from one cave to another. Because bats are highly social, there is a great potential for rapid devastation.

Meanwhile, scientists are looking for treatments. Of 1,900 different compounds tested, most had no effect, some actually promoted the growth of G. destructans, and a few did inhibit growth and some even killed it. Applying the treatments to caves, however, is another matter. Chemical treatments could negatively impact a non-target species.

It’s hoped that—like the bats in Europe may have done—our North American bats will develop a way of dealing with the disease on their own, whether that comes from an immune-system response, behavioral changes, or a combination of the two. Survivors that are immune could produce offspring that are resistant, and, although it would take decades, bat populations may eventually rebound.

Another option is captive assurance and propagation, in which large numbers of bats would be kept in captivity, reproduce, and eventually be released into the wild. Bat World is working with bat care specialists throughout the U.S. to provide specialized training to others interested in maintaining captive assurance colonies, and to expand operations.

Helping Bats in Northern Virginia

Bat World Northern Virginia organizes bat rescue and rehabilitation, as well as outreach and education. Leslie Sturges is a full-time volunteer who leads the group. The local chapter rehabilitates 50-80 bats each year, many of which end up in Leslie’s basement. She uses 2-3 pairs of gloves to ensure that she doesn’t get bit – wild bats don’t like being handled! Here are her suggestions for how we all can help protect bats.

- Make sure that any pets have up-to-date rabies vaccinations, including indoor cats.

- If you find a bat in your home, do not touch it with bare hands!

- Why? If an errant bat finds its way into your home and touches your bare hands or your unvaccinated pet, the bat must be taken to be tested for rabies. Sadly, the test requires killing the bat.

- Speak truth about bats and other wildlife. Don’t make up stories! We are the top predators in our world, and we are not victims. There is much cruelty inflicted out of fear.

- Homeowners are encouraged to be tolerant of bats if you find them in your house during maternity season, from May to August. It may be disturbing to have bats come and go for a few months, but the babies have just been born and cannot yet fly on their own. It’s best to wait until September, then exclude them from the house humanely and seal off the entrance. Provide replacement habitat by putting up a bat box.

- A recommended resource for tips and information, including how to install a bat box: http://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/Plants_Wildlife/bats/

- If you are interested in learning more about how you can help as a volunteer or supporter, contact Leslie: bwnova@batworld.org or 703-973-3157.