By Jessica Hudson, Director, Fairfax County Public Library

Kevin Osborne, Deputy Director, Fairfax County Public Library

Dianne Coan, Division Director, Technical Operations, Fairfax County Public Library

Banned Books Week is an annual celebration of the freedom to read sponsored by a coalition of organizations including the American Library Association. With discussions around the availability of materials making the news and locally, we thought now would be a good time to delve into the issues that surround challenging and banning books.

Meeting Community Needs

Libraries provide educational, informational and recreational materials for their communities; Fairfax County Public Library (FCPL) is no exception. In recent years and in support of our community and the county’s One Fairfax initiative, FCPL has expanded its collection to better reflect the community’s demographics. We’ve worked to include more world languages and books from authors who reflect the county’s rich diversity of ancestry, traditions and lived experiences.

Offering a broad collection while staying in budget is not our only challenge. Curators have long faced a dearth of published materials that reflect our nation’s population. Between 1950 and 2000, Black and other novelists of color represented only 10% of all book reviews, less than 2% of U.S. best-sellers and 9% of U.S. literary prize winners, as Richard So shows in the introduction to his book Redlining Culture: a Data History of Racial Inequality and Postwar Fiction.

More recently, both a New York Times article published by So and Gus Wezerek and the Lee & Low review of diversity in publishing show little has changed in the last two decades. The books released by the country’s primary publishers largely reflect an ongoing disparity between the number of white authors published and the number of authors of color published. This disparity and fewer marketing dollars invested by publishers make it harder for buyers to discover authors and high-quality books from smaller presses. Once included in libraries’ collections, these same books authored by people from non-dominant communities face a disproportionate number of calls for libraries to censor.

Are we talking about censorship?

Merriam-Webster defines censoring as “to suppress or delete anything considered objectionable.” The American Civil Liberties Union expands on this, stating that “censorship, which is the suppression of words, images, or ideas that are ‘offensive,’ happens whenever some people succeed in imposing their personal political or moral values on others.” Individuals or private groups publicly objecting to a book, such as organizing a boycott, is substantially different than when it’s done by the government. A boycott’s success or failure can be considered an economic outcome of market forces at work. The latter is unconstitutional, an illegal abridgement of First Amendment rights, with narrow exceptions. Though U.S. public libraries face many first amendment rights issues, the most prominent is the call to ban books.

It’s also important to address some other words associated with books considered controversial: challenging and banning. A challenge refers to an attempt to remove or restrict. Books might be challenged by a citizen, an organized private group or another entity. But books are only considered “banned” once a previously available book is taken off library shelves because of its content.

Historical context

According to historians, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the first book in the United States banned on a national scale. Critics banned it for holding pro-abolitionist views and causing divisive debates on slavery. As First Amendment Scholar David L. Hudson, Jr. notes, books that arouse debates or contain controversial ideas are often the target of banning, but that discussing controversial ideas is the key to education.

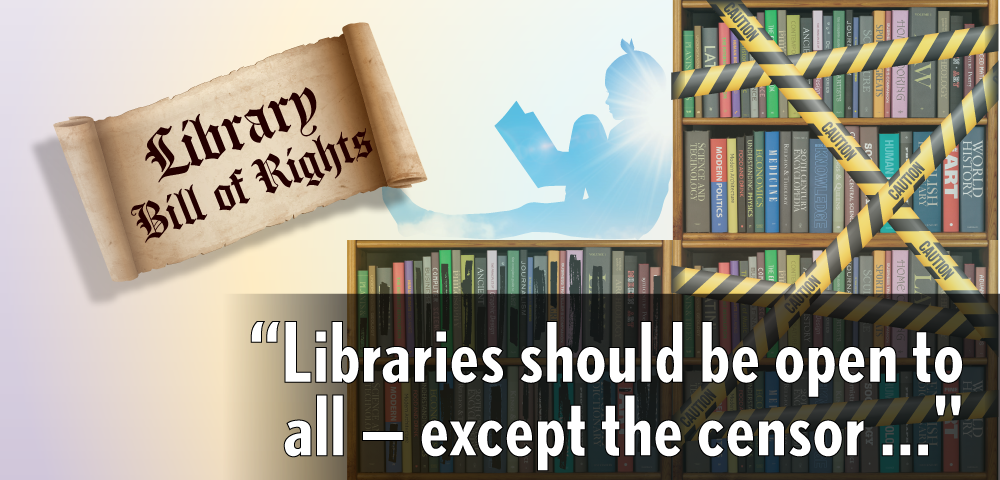

The first article of the Library Bill of Rights adopted by the American Library Association (ALA) in 1939, and reaffirmed as recently as 2019, states that books should not be excluded simply because of the origin, background or views of those contributing to their creation. The second article reads in its entirety “Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

The Library Bill of Rights also calls for libraries to challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and to ensure they have materials that reflect their communities. In its 1982 Island Trees School District v. Pico decision, the Supreme Court affirmed that the right to receive information is a fundamental right protected under the U.S. Constitution when it held “the right to receive ideas is a necessary predicate to the recipient’s meaningful exercise of his own rights of speech, press, and political freedom.” This decision held that books cannot be removed from a library based on partisan or political grounds, which would be tantamount to a government-sanctioned suppression of ideas – censorship.

Current Issues

According to ALA’s latest State of America’s Libraries Report, librarians faced an unprecedented number of book challenges in 2021. Across the U.S., the most targeted books were by or about Black or LGBTQ+ persons. Opponents frequently cited obscenity in their challenges. Legally, obscenity requires the work lack “serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” This is a higher standard than the more common use of the word meaning repugnant, a distinction sometimes lost in the rhetoric.

"Libraries must be open to all … “

Books banned at any point are important guideposts in our understanding of censorship. Having the historical context of the time and place of when a book was banned helps us learn about the society responsible for their censoring. As society evolves, so does what it considers to be appropriate reading. Libraries, by reflecting their communities and providing multiple perspectives on a topic, ensure availability of what some may consider unorthodox or unpopular ideas to anyone who wishes to engage with them.

In the words of President John F. Kennedy, “If this nation is to be wise as well as strong, if we are to achieve our destiny, then we need more new ideas for more wise men reading more good books in more public libraries. These libraries should be open to all — except the censor. We must know all the facts and hear all the alternatives and listen to all the criticisms. Let us welcome controversial books and controversial authors. For the Bill of Rights is the guardian of our security as well as our liberty.

FCPL’s staff, our collection, our events and our services reflect our community. Our library re-commits to ensuring perspectives from many points of view, so we can support the precept: for every book its reader, for every reader their book.