Local Climate | The Shape of Your Land

"Within is a country that may have the prerogative (advantages) over the most pleasant places known, for large and pleasant navigable rivers, heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation...Here are mountains, hills, plains, valleys, rivers, brooks, all running most pleasantly into a fair bay, compassed but for the mouth, with fruitful and delightsome land...."

Captain John Smith, writing about Virginia in his 1624 book, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles

Virginia is blessed with a temperate climate, moderate rainfall, and a rich and varied topography. Although August sometimes feels unbearable in its humidity and January endless with its ice and snow storms, these extremes ensure that Virginians may enjoy all four seasons of the year. Who would trade Virginia’s glorious and extended spring and fall seasons for anything else? These conditions also present you with an extensive plant palette. Without the January freeze, no apple trees would thrive. Without the warmth of the remaining seasons, camellias, cantaloupes, and persimmons would be lost.

LOCAL CLIMATE

Temperature, rainfall, and wind are the most important aspects of climate, with temperature being the most critical factor. Low temperatures late in the spring can destroy a fruit crop. Unusually low temperatures in the winter may kill plants that are marginally hardy in Virginia. There is a wide variation in average temperatures across the Commonwealth, affecting the growing season and your heating and cooling bills. Temperature variations are affected by your land’s geographic position. The temperature variations on land adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean are more moderate than the temperature variations at the peak of the Blue Ridge. Within these geographic areas, temperature variations are also affected by the location and shape of a site. The midslope of a hill has the most moderated temperatures on a hillside. Look at a hillside and notice the location of the first blush of light green when trees leaf out in the spring, or notice where the trees first begin to turn color in the fall. Remember that cold air drains down the drainageways just like water, creating small frost pockets in its wake.

ZONE MAPS

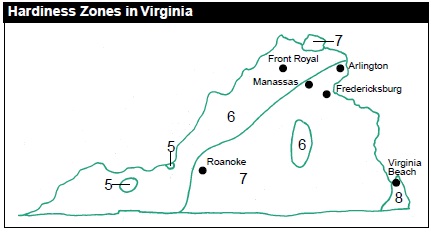

Plant hardiness maps have been developed for all of North America by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Divided into 10 hardiness zones, these colorful maps are found in most plant books. Knowing the zone number for your part of Virginia will help you determine which plant will thrive where you live. Virginia falls within Zones 5, 6, 7, and 8. This means that plants native to the Pacific Northwest’s Willamette Valley (Zone 7) will thrive in portions of Virginia. Plants native to eastern Wisconsin, Illinois, and Massachusetts (Zone 5) may also thrive — although some may find Virginia too warm — providing you with an extensive plant list from which to choose.

MICROCLIMATE

Hardiness zones can be expanded or reduced by manipulating the microclimate of a site. You can provide wind protection for a plant or make use of a heat-absorbing wall or brick terrace for reflected and stored warmth. The sun’s position changes with the seasons, affecting the amount of shade your garden receives. In summer, the sun is high in the sky and casts short shadows. In winter, the sun is low and produces long shadows. Study and chart your sun and shade patterns daily and seasonally. You may also manipulate these patterns by building structures. A broad eave or trellis will provide shade and create a microclimate.

PRECIPITATION

Much of the precipitation that falls to the earth either evaporates back into the air from the plants and ground surface or infiltrates down through the soil into the groundwater. The remainder of the water runs across the surface of your land into storm drains, streams, rivers, and lakes as surface runoff. Once in the stream channel, it is joined by subsurface flows at locations where the groundwater surfaces.

PREVAILING WINDS

The prevailing weather pattern for Virginia in the summer and fall is from the south Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. Warm, moist air brings thunderstorms and higher humidity. In fall, cooler air from the north and west returns. Winter weather blasts across the state from the northern or central part of the continent.

Plants benefit from a cooling breeze on a hot day, just as you do. Wind keeps your garden’s air circulating, preventing pockets of stagnant air, drying off the morning dew, and reducing fungal growth on your plants. Wind can also harm your plants. Too much, and the soft-wooded tree splits, or the delicate leaves are shredded. Wind can also dehydrate the leaves of the plant. If your home is on a windy hillside, your garden may be a zone colder than the area in the valley below. Knowing your prevailing wind patterns will help you avoid creating wind tunnels or exposing vulnerable plants to inhospitable conditions.

HUMIDITY

Humidity is the moisture in the air and soil. Plants that are happy in your summer garden most likely thrive in high humidity. Choose fungus- and mildew-resistant plant strains and provide your garden with good air circulation by giving each plant adequate space to flourish.

Return to Index at top of page

THE SHAPE OF YOUR LAND

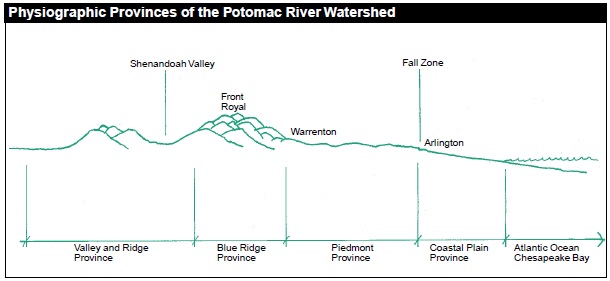

Scientists have classified Virginia and the rest of the United States into physiographic provinces. These provinces describe the shape of the land (hilly, mountainous, or flat); the type of rock found within it (sandstone, limestone, or granite); and the type of soils commonly associated with it. Four physiographic provinces are found in the Potomac River watershed in Virginia.

COASTAL PLAIN PROVINCE

Millions of years ago this area was underwater, with the Atlantic Ocean extending west where Interstate 95 is now located. Today the land is flat to rolling and is crossed with broad, slowly moving rivers and streams generally flowing eastward toward the Atlantic. Soils in this area are frequently referred to as unconsolidated and are comprised of layers of sand, silt, clay, and gravel originally deposited by ancient oceans and rivers. Many of the soils in the Coastal Plain are poorly drained and include “marine clay” or “blue clay,” soil types that require specialized construction knowledge. These soils shrink when dry and swell when wet, putting great pressure on building foundations.

FALL ZONE

The fall zone of Virginia’s rivers is located at the juncture of the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont Provinces. Rivers that are broad and slowly flowing in the Coastal Plain are narrow and filled with rapids and falls in the Piedmont Province. The change from tidal to nontidal is reflected in the creatures that live in and along the water. When Virginia was first settled by Europeans, many of its river-sited cities were located at the farthest point where ocean sailing boats could travel upstream. Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River, Richmond on the James River, and Petersburg on the Appomattox River are located at the fall zone. Historic Georgetown in Washington D.C. is located at the fall zone of the Potomac River, with Great Falls, Virginia, just upstream.

PIEDMONT PROVINCE

The Piedmont is the largest physiographic province in Virginia and extends from the Coastal Plain to the Blue Ridge. The shape of the land is rolling and forms the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Piedmont upland is dominated by ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks, and the lowlands have soils overlying shallow sedimentary rocks and igneous intrusion.

BLUE RIDGE PROVINCE

If you have ever hiked in the Blue Ridge Mountains, you can easily remember the shape of the land in this province. The steep slopes, stoniness of the soil, and the shallow depth of soil above rock demand that careful attention be given to minimize erosion. Soils in this province are derived from a combination of sedimentary rocks, rocks formed directly from the molten magma, and rocks formed by heat and/or pressure. In general, the sedimentary rocks are on the west side of the Blue Ridge, and the igneous and metamorphic rocks are on the east side.

VALLEY AND RIDGE PROVINCE

This province is primarily composed of sedimentary rocks such as limestone, shale, sandstone, and conglomerates. The depth of the soil varies tremendously. Sinkholes occur in this area due to the nature of the bedrock.

LANDFORMS

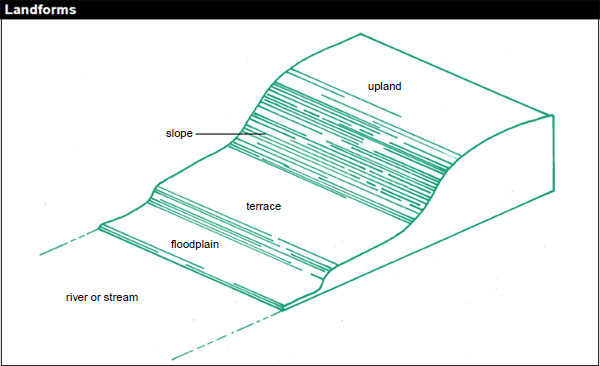

Your yard, pasture, and common lands are located on hills and valleys, on floodplains and uplands, and on the slopes between. These places have distinctive shapes that provide clues to the type of soil conditions you are likely to encounter, what plants will thrive, and what potential erosion and drainage problems you may experience. Soil surveys classify the soils in association with their location on the particular shape of the land, or landform. Typical soils in the Potomac River watershed include Fairfax, Calverton, and Mecklenburg.

Floodplain: The floodplain is the area adjacent to the stream channel that is periodically inundated with water. Wetlands and floodplains also provide natural floodwater storage, and their vegetation physically slows the speed and turbulence of floodwaters.

Terrace: A terrace is an old alluvial plain that is usually flat and borders a river, lake, or ocean.

Slope: Slope describes the tilt of the land. Slopes influence land use and various environmental components of the landscape. Stormwater runoff rates are higher on steep slopes, and the performance of septic drainfields for residential sewage disposal declines with steeper slopes.

Upland: An upland is generally higher in elevation than the floodplain or terrace.