Children catch stream bugs. Always wash your hands after playing in the stream.

Credit: Christin of "Wandering thru"

Stream Restoration and Fairfax County Watershed Management Plans

By Adele Kuo

Our neighborhood streams and creeks draw people of all ages, especially our children, to play at the water’s edge. Exploring a small stream stimulates all the senses: it provides the delightful burbling of water trickling over stones, small pools that twinkle with reflected light, and the melodic chorus of the aquatic life. There are mosaics of natural outcroppings of stones and plants, fresh air mixed with wholesome earthiness, and cooler waters that soothe bare feet. Aquatic vegetation creates hiding places where small critters can be discovered going about their daily activities. Healthy streams provide the priceless simple pleasures of exploring nature and deciphering the surrounding natural environment, even in the midst of our increasingly built-up world.

What is Stream Restoration?

Stream restoration can take on many forms, and is one of many new technologies and creative planning tools that can be used to protect watersheds. Restoration may include practices such as replanting native vegetation along stream banks, fencing out livestock from the stream channel, or reshaping the channel to create a stable stream using natural channel design.

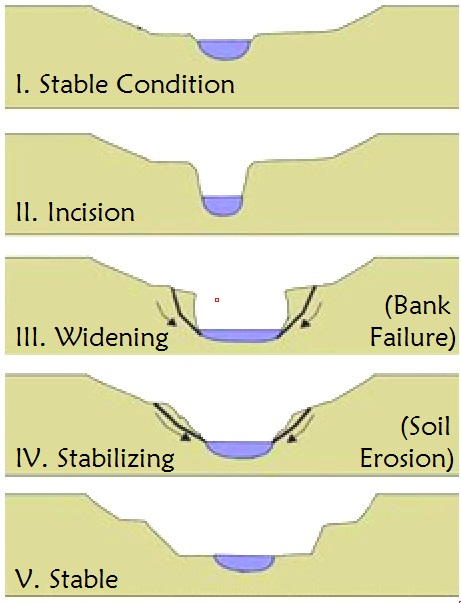

Stream channel evolution in response to increased runoff

Natural channel design seeks to restore the disturbed stream to emulate the natural stable channel. Stream bank erosion is a natural process, but can be accelerated by human impacts. When we build roads, buildings, and parking lots, we increase impervious surfaces, and more runoff rushes to streams when it rains instead of soaking into the land. Stream banks are eroded and channels are deepened and widened. Tree roots are exposed and the incising stream channel becomes disconnected from its floodplains. Stream buffer zones are impacted, trees fall and die, and without them soil is left to erode away. Over time, a new deeper and wider channel will form, and the stream vegetation will recover, but not before rain carries away huge amounts of sediment.

A stream restoration that uses natural channel design will imitate nature while preventing soil erosion. The incised stream channel cross section is re-graded to a more gentle angle to accommodate plantings, improve bank stability and reconnect a stream to its floodplain. Because redesigning streams often removes trees along the stream edge in order to accommodate the wider channel, stream restoration can sometimes cause controversy. Unfortunately, if the stream is left to restabilize on its own in response to increased runoff flow, the trees will come down regardless, but with much more soil erosion damage to the watershed. Although natural channel design projects can be expensive, conventional approaches of armoring banks with rock rip-rap, berming and concrete channelization can be many times more expensive and negatively impact aquatic habitat and the downstream channel.

Across Fairfax County, a pleasant stroll through a typical suburban community passes sidewalks, streets, homes, and well-kept lawns. Though it may not seem so, our neighborhoods are directly connected to those stream ecosystems. The storm drain network, the traditional way of handling rainfall, sends runoff directly to the streams through concrete channels and pipes. This prevents street flooding, but has environmental consequences. In natural systems rain soaks into the soil, recharging groundwater, but when rain falls on impervious surfaces like roads, rooftops, and parking lots, it all turns into runoff.

As a result, when it rains, runoff from the storm drain system overwhelms our streams. The runoff carries eroded soil particles, yard debris, trash, oil, and harmful nutrients and chemicals from lawn care. Water temperature fluctuations impact the ability of fish, amphibians, and insects to survive or reproduce. The increased quantity of water flow causes stream bank erosion and other physical changes. Our urban streams suffer from runoff pollution, erosion, and degradation.

Many residents have witnessed these events occurring in the streams that pass through their backyards and neighborhoods. Virtually everyone living in Fairfax County lives within a half-mile of a stream or creek, and all Fairfax County streams eventually flow into the Potomac River, Chesapeake Bay, and Atlantic Ocean. What happens in your yard and neighborhood, or on any parcel of land, affects the water quality downstream, which in turn affects us all. Habitat is damaged, recreational and aesthetic value is diminished, and more resources are needed to treat drinking water.

In 2003, Fairfax County embarked upon a long-term project to develop comprehensive Watershed Management Plans for each of the county’s watersheds. Over one million people live in the county’s 400 square miles. This area is drained by 30 major watersheds – such as Accotink Creek, Difficult Run and Bull Run, to name just a few. The 30 watersheds contain 980 miles of streams that are as diverse as the communities that inhabit them, yet they all drain to the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. No matter where you live, work or play, you are connected to everyone else through your watershed.

The Fairfax County Watershed Management Plans will serve as tools to identify and address the issues affecting our environment and to manage the protection, conservation, and restoration of the county’s stream corridors, wetlands, and other water resources. As of February 2011, all the Watershed Management Plans have been approved by the Board of Supervisors. The plans are facilitated by the Stormwater Planning Division of the Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services (DPWES).

As part of the Watershed Management Plan process, a small tributary of Big Rocky Run was targeted for stream restoration. A successful stream restoration attempts to find a stable equilibrium between the stream’s ecological functions and the urbanized landscape that surrounds it. (Read more about stream restoration in the box above and follow the process in photos below.) The primary goals of the project included stabilizing eroding stream banks and re-establishing a vegetated buffer to improve the stormwater drainage from a subdivision across a wide, busy road. To view the Watershed Management Plans that include streams near you or to learn more about your watershed, visit www.fairfaxcounty.gov/dpwes/watersheds/.

Over the last decades, the way rainwater is handled has changed. As the Watershed Management Plans emerge and begin to be implemented in Fairfax County, the health, safety, and function of our watersheds will continue to play a larger role in the way we plan and manage our surroundings. We find that stormwater can behave naturally despite imperviousness and other challenges, and that stream restoration projects celebrate the rebuilding of a stream to a more stable condition. Improving the overall health and ecological character of streams in the midst of suburban Fairfax County invites residents of all ages to amble down to the water’s edge and enjoy their alluring qualities.

Before Restoration (View 1)

During Restoration (View 2)

Right After Restoration (View 2)

After Restoration (View 1)

Stormwater Planning Division, Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services

Adele Kuo is a graduate student at George Washington University pursuing a degree in Sustainable Landscape Design.