By Maddie Ryan and Jessi Ende

Have you ever thought about where the water that we use for drinking, cooking and cleaning comes from? How does it get to our homes?

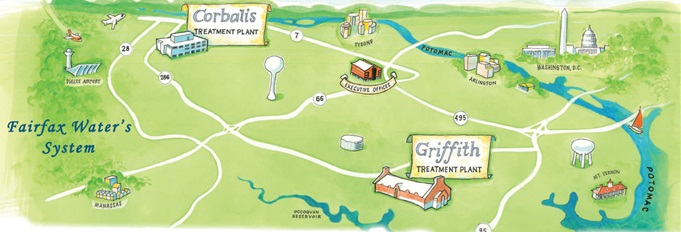

In Fairfax County, our water comes from two major sources: the Occoquan Reservoir and Potomac River. The water that flows in the Potomac and Occoquan comes from both groundwater and stormwater runoff.

Groundwater is cleaned and cooled when it flows through the soil. Runoff, on the other hand, can carry pollution into our drinking water sources, including sediment from the land, contaminants such as pesticides or motor oil, and organic matter from deceased insects, plants, or animals. Water treatment plants remove these impurities and make the water safe for household use.

The Occoquan Reservoir provides drinking water supply to Northern Virginia through the Fredrick P. Griffith treatment plant. This plant can treat up to 120 million gallons of drinking water per day.

The Potomac River provides water to area residents through the James J. Corbalis Jr. treatment plant, which can treat 225 million gallons of water per day.

Fairfax Water operates both the Corbalis and Griffith treatment plants. In January 2014, Fairfax Water acquired the water systems of the City of Falls Church and City of Fairfax. Portions of these systems rely on water from the Washington Aqueduct.

The Potomac River is also the source of water for the Washington Aqueduct, which operates the McMillan and Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plants. These plants together can produce 300 million gallons of water per day.

Two million people in Northern Virginia are now served by Fairfax Water.

Turning River Water into Drinking Water

How do the treatment plants make raw water from the Potomac and Occoquan drinkable?

Intake

Water from the Occoquan Reservoir and Potomac River flows into intake pipes underground. Screens prevent fish and large sediments from entering the intake pipes. This water is pumped through a raw-water pumping station into the treatment plant.

Coagulation

Chemicals called coagulants, such as alum, are added to the raw water and adhere to any contaminants in the water, such as sediment or waste.

Flocculation

As the coagulants bind to the contaminants, they create larger particles called floc. These particles group together to become heavier and eventually sink to the bottom of the receiving basin.

Sedimentation

The floc particles settle to the bottom of the sedimentation basins. Giant paddles sweep the bottom of the basins to direct the sediment into a hole at the bottom of the basin. The sediment is taken to a machine that squeezes the water out of the sediment to create large, flat "cakes" of mud. This mud is taken to farmers to be used for growing crops.

Ozonation

In some treatment systems, the water left in the basin during the sedimentation phase is pumped into large tubs for ozonation. In this process, ozone is added to the water for disinfection.

Filtration

The water is then filtered through layers of sand and carbon. At this point, the treatment process has removed contaminants, bacteria and pollutants and the water is nearly ready for distribution.

Disinfection and Distribution

The final step in the water treatment process adds fluoride to protect teeth and chlorine to protect the water as it travels through the distribution system to each home. A corrosion inhibitor is added and the pH is adjusted to help prevent lead from leaching into the water from household plumbing. This treatment process ensures that the water surpasses federal and state standards.

Well Water

In some areas of Northern Virginia, water from the public systems are not available. Instead, homes are supplied with well water, which comes directly from groundwater, not a treatment plant.

Emerging Contaminants

Drinking water quality is very tightly regulated by the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the Virginia Department of Health works to ensure compliance. Highly trained laboratory staff at treatment plants use state-of-the-art equipment to monitor water quality around the clock.

In recent years, new emerging contaminants like endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs), medicines and personal care products have become a concern, especially after a study conducted in the Potomac River found intersex fish.

In addition to testing, laboratory staff also conduct research on emerging water quality issues, including pharmaceuticals and disinfection byproducts. So far, studies have shown that currently available treatment technologies are effective in removing broad categories of EDCs, personal care products and pharmaceuticals.

Water treatment scientists and staff in the region and across the nation are studying and closely following the research on emerging water quality contaminants, and will continue to use the results to guide management decisions.

How You Can Help

There is much that we all can do to help protect our source water, the Potomac and Occoquan Rivers. As the county’s population continues to grow, there will be a greater demand for drinking water. At the same time, increased pressure for development will affect our rivers.

Preventing water pollution and reducing runoff can be easy. Put expired pharmaceuticals in the trash, not down the toilet. Keep car wash suds and other chemicals out of the storm drains and local streams. Use a rain barrel or rain garden to capture and reuse rain water. Plant trees. Taking these actions will help protect our health as well as the health of the natural world.

What Happens Next? Learn about where our wastewater goes.

Jessica Ende is a geology student at the University of Rochester. Madeline Ryan is an environmental science student at Virginia Tech.

Image credits: Corbalis and Griffith Treatment Plant Map Artwork created by Jean Gralley.