By Devy Jagasia

Have you ever thought about where our water goes when we finish taking a shower or after we have washed the dishes? Not many of us think frequently about what happens to our water after we are done with it. Our wastewater goes through a rigorous treatment process after we have finished washing, bathing or cooking.

But why treat wastewater? Clean water is critical for fish, wildlife, and for health safety reasons. When treated wastewater is discharged back into our rivers, the fish and other aquatic wildlife that depend on these waterways are in direct contact it. (Unlike water from your kitchen sink, rainwater entering curbside storm drains is piped directly to the nearest stream, and that runoff is not treated. Only rain in the storm drain!)

Many pollutants present in wastewater can negatively affect ecosystems and human health:

- Decaying organic matter and debris can use up dissolved oxygen so fish and other aquatic biota cannot survive.

- High concentrations of nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) lead to over-fertilization of receiving waters. This causes huge algae blooms which reduces available oxygen, harms spawning grounds, alters habitat and leads to a decline in key species. Ammonia, a form of nitrogen, can be toxic to aquatic organisms.

- Chlorine compounds and inorganic chloramines can be toxic to aquatic invertebrates, algae and fish.

- Bacteria, viruses and disease-causing pathogens can pollute beaches and contaminate shellfish populations, leading to restrictions on human recreation and shellfish consumption.

- Metals, such as mercury, lead, cadmium, chromium and arsenic can have acute and chronic toxic effects on wildlife and human health.

So how do we get rid of these contaminants? There are three main processes for preparing wastewater for discharge.

Primary Treatment: Sedimentation and Screening of Large Debris. First, the liquid is separated from the solids using screens and large settling tanks. Water passes through sand and gravel and heavier solids are filtered out.

Secondary Treatment: Biological and Chemical Treatment. Secondary treatments vary from one treatment plant to the next, and usually include biological and/or chemical treatment. One of the most common biological treatments is the activated sludge process, in which primary wastewater is mixed with bacteria that break down organic matter and clean the water. Oxygen is pumped into the mixture. A clarifying tank allows sludge to settle to the bottom and then the treated wastewater moves on for tertiary treatment.

Tertiary Treatment: Advanced Treatment. Coagulation, filtration and disinfection take place in tertiary treatment. A coagulant, such as aluminum sulfate, is added, causing suspended particles to consolidate and settle. Filtration removes organic matter, microorganisms and mineral compounds, keeping excess nutrients out of rivers and wildlife habitat. The water is chlorinated or ultraviolet rays are used to kill any remaining bacteria. After, a solution is added to remove residual chlorine.

These processes clean out suspended solids, pollutants, metals, pathogenic and non-pathogenic microorganisms, organics, as well as nitrogen and phosphorus. In our area, the wastewater is then discharged to either the Occoquan or the Potomac River, which flows to the Chesapeake Bay.

Since 1972, U.S. rivers, lakes, and streams have been protected through the Clean Water Act. The stated objective of the act is “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters.” The Clean Water Act established specific national goals concerning the health of United States surface waters, enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). As wastewater treatment plants get older and new technologies become available, plants are required to improve the quality of the water they discharge.

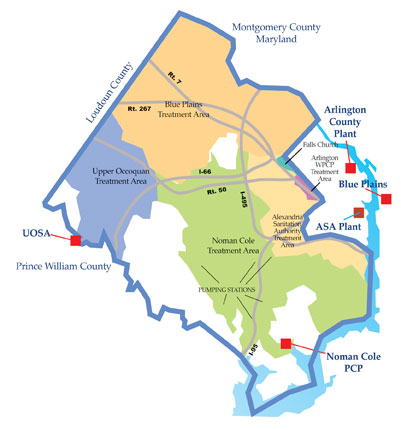

There are five main treatment plants handing wastewater from Fairfax County residents. Each plant has taken steps to increase capacity and improve water quality to handle population increases and tighter standards. Many of our local treatment plants bring home top awards for superb water treatment!

1. Noman M. Cole, Jr. Pollution Control Plant. In Lorton, Virginia, bordering Pohick Creek, Fairfax County’s Noman Cole Pollution Control Plant has been in operation since 1970. The Noman Cole plant is the primary recipient of Fairfax County wastewater, treating 67 million gallons of Fairfax County wastewater per day or 42%. Go to: and search for Noman M. Cole, Jr. Pollution Control Plant.

2. Alexandria Renew. Near the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, the Alexandria Renew Enterprises plant takes in wastewater from the city of Alexandria and a portion of Fairfax County. Water is discharged into Hunting Creek - Cameron Run at the Potomac River. This plant treats 32.4 million gallons of Fairfax County wastewater per day or 20%. Go to: Alexandria Renew.

3. Blue Plains Treatment Plant. Located on the southernmost tip of the District of Columbia, the Blue Plains Treatment Plant takes wastewater from D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, including a portion of Fairfax County. In operation since 1938, Blue Plains today is the largest advanced treatment plant in the country, with a total capacity of 370 million gallons per day. The plant treats 31 million gallons of Fairfax County wastewater per day or 19%. Go to: Blue Plains Treatment Plant.

4. Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority. Adjacent to Bull Run Regional Park, the Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority plant was formed in the 1970s and serves jurisdictions in the Occoquan watershed: Fairfax County, Prince William County, Manassas and Manassas Park. Importantly, the sewage plant is upstream of the Occoquan Reservoir, where a good portion of southern Fairfax County’s drinking water comes from. This plant treats 27.6 million gallons of Fairfax County wastewater per day or 17%. Go to: Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority.

5. Arlington Water Pollution Control Plant. At Four Mile Run and the Potomac by Reagan National Airport, the Arlington plant treats water from Arlington, Alexandria, Falls Church, and Fairfax County. This plant treats 3 million gallons of Fairfax County wastewater per day or 1.9%. Go to: Arlington Water Pollution Control Plant.

Others include the Prince William County Service Authority, which treats 100 thousand gallons of wastewater per day from Fairfax County, or 0.06%; as well as Colchester, a private wastewater treatment plant (80 thousand gallons per day for Fairfax County, or 0.05%).

Many of the treatment plants also provide tours, which are not as malodorous as you might think! More information is available at the websites above.

Devy Jagasia is a graduate student in Environmental Science at George Mason University.