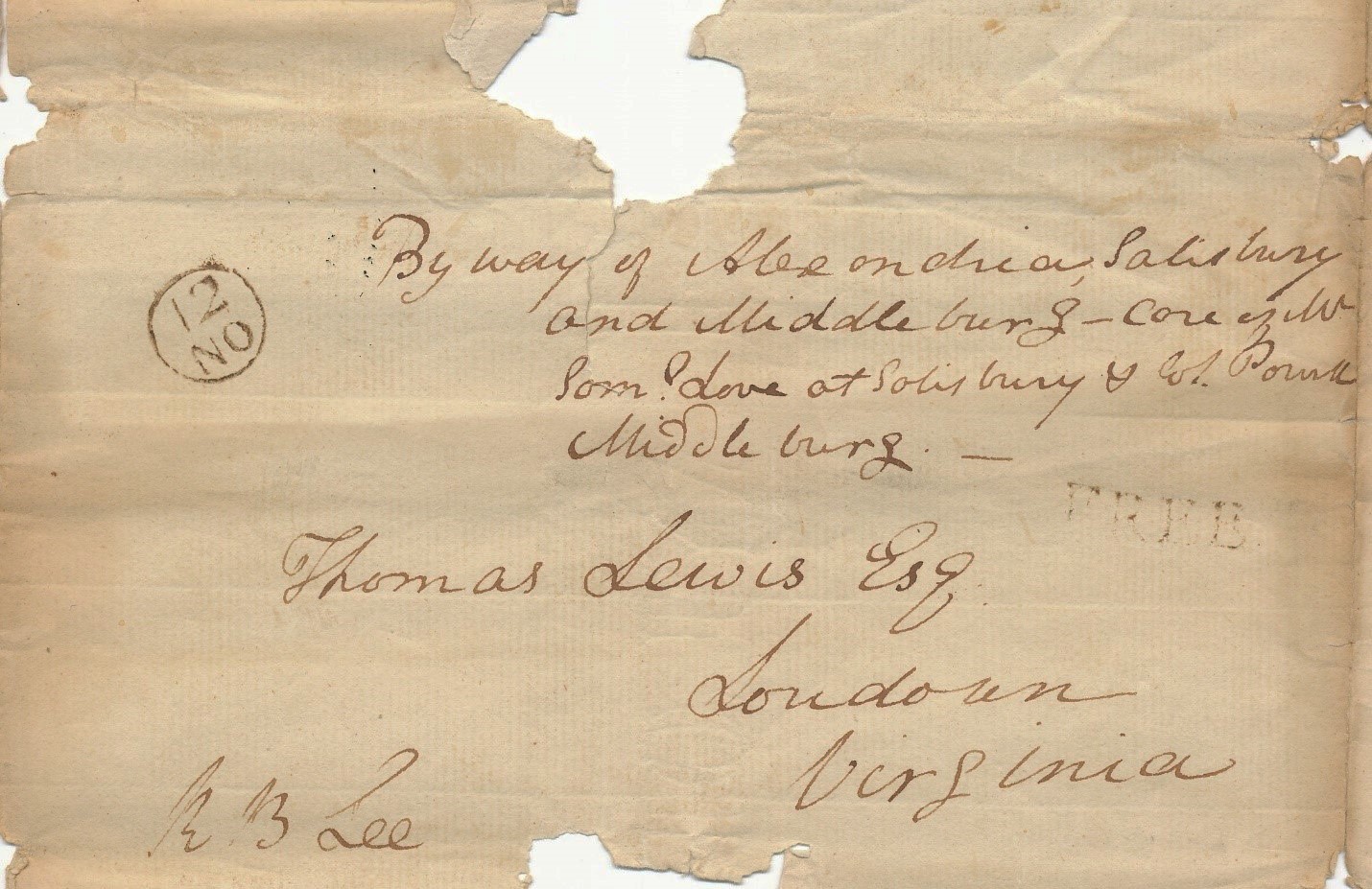

An envelope in the Park Authority’s historical collection reminds us of the importance of mail in an era before electronic communications.

No governmental agency is as bound to origins of our nation as closely as the United States Postal Service. The idea of this office, in thought and practice, predates the US Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. The goal was to use this service as a way to connect the people scattered across the land and provide them with a dependable way to receive goods and information to result in an informed electorate. The development of reliable transportation systems, including roads, stagecoaches, steamboats, trains, and planes, are tied to it. These advances were seen as vital to the continuing development of our nation.

Its first official iteration was the Constitutional Post, which began in 1774 as a response to mistrust in the British-run Parliamentary Post. Colonists felt the Parliamentary Post was another form of taxation to which they did not consent. In addition, they did not like that it was not private, as postmasters were allowed to intercept and open letters, which could have hindered revolutionary activities.

Benjamin Franklin was appointed the first postmaster general at the Second Continental Congress in 1775. One interesting feature of this system that dates back to this time is franking privilege, which allowed certain people to send mail without postage. The idea for this came from the British House of Commons, which instituted a similar system in 1660. The term comes from the Latin “francus” which can be interpreted to mean “free.”

In the United States, this privilege was given to many government positions, including members of Congress. Between 1789 and 1792, Congress passed three temporary Post Office Acts that allowed this privilege to government offices and officials. It was the central way for members of Congress to convey information to their constituents.

The envelope in the above photo dates to November 12, 1792. During this time, Richard Bland Lee, of what is the now Sully Historic Site, was serving as the first representative of Northern Virginia in the House of Representatives, which gave him franking privileges. The Postal Act of 1789 required the sender to personally add their signature to the envelope, as can be seen here, along with the faint word “FREE.” This condition was later changed as there were reports of some members spending three hours a day signing their names to envelopes.

The Postal Act of 1789 also temporarily established The United States Postal System before it was permanently established in The Postal Act of 1792. Today, franking privilege still exists in some form, though over the years the parameters of this privilege have fluctuated, and it is often pointed to as an indication of governmental waste.