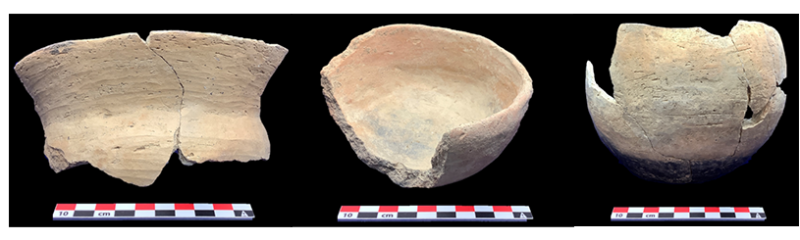

Colonoware. Most of us outside the world of archaeology have never heard that name, but to those in the field these vessels tell a story about necessity and provide an interesting link to the story of enslaved individuals. The artifacts pictured here are vessels of a ceramic type known as colonoware that were recovered from the Lyndam Hill archaeology site in Fairfax, Virginia. Lyndam Hill is one of 16 documented sites in the County where over a thousand colonoware vessel fragments have been recovered and preserved by archaeologists. So, what is colonoware, why is it found in our community and what can it tell us about the lives of past inhabitants?

In 1962, British archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume was conducting archaeological investigations at Colonial Williamsburg when he first discovered and identified a new ceramic type. Hume called the new ceramic Colono-Indian ware and described it as “markedly inferior to even the cheapest type of colonial lead-glazed earthenware.”1 He concluded that this ceramic type was made by Native Americans and sold to be used by enslaved African Americans. He believed this because these wares were not like other higher quality ceramic vessels and dishes used during the time. They appeared to be similar to ceramics made by local native people. Later discoveries in South Carolina of ceramics with the same form shifted this interpretation to the more currently accepted theory that these types of ceramics were produced by the enslaved and used in their daily lives. Archaeologist Leland Ferguson compared the shape of these vessels and those found in Williamsburg to vessels produced in Ghana and Nigeria and recognized that these had more similarities than those produced by local Native Americans. While archaeologists continue to study and debate the origin of colonoware, it is clear that the production, trade, and use of this ceramic type was defined by many complex cultural relationships.

This style of ceramic, now commonly referred to as colonoware, is made of locally sourced clay fired at a low temperature to create an unglazed, course earthenware dish or vessel that is often buff in color. Typically, decoration or embellishments were not added to these ceramics. However, occasionally pieces have been found with incised patterns or the potter’s name impressed upon the surface. The low-quality material and cheap manufacture produced inexpensive vessels meant for everyday use when cooking, cleaning, or transporting goods. Colonoware bowls, plates, jars, and even chamber pots have been recovered from different archaeological sites dating from the 17th to 19th centuries.

Numerous colonoware vessels have been archaeologically recovered from enslaved contexts within plantation sites across the southeastern United States and Caribbean islands. Some have been discovered in North Carolina and Georgia, but the known majority come from Jamaica, South Carolina, and Virginia. It is important to recognize that these artifacts are not part of African culture but are a product of what was available to people enslaved and not used by choice or preference. Colonoware is not found at historic sites which are the homes of free Black Americans. Colonoware was not a desired ceramic type and was used only out of necessity with production ceasing at the end of the Civil War, by which time most enslaved Virginians were emancipated. Fairfax County archaeologists have recovered numerous quantities of colonoware vessels and vessel fragments from local sites which are preserved and stored in the county’s collection facility for future researchers to continue to learn and understand our past.

1 Hume, Ivor Noel. 1962. An Indian Ware of the Colonial Period. Quarterly Bulletin – Archaeological Society of Virginia 17:2-14.